Panificio Il Magnifico

Our History

Ancient ingredients, skilled hands, superfine products!

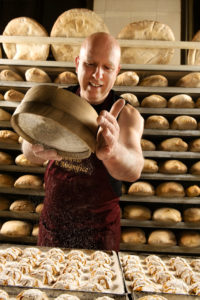

Lorenzo Rossi, 48, has been a baker since he was 17. School, the one with benches, did not attract him like the family bakery in the historic centre of Siena. The hard work of father Giorgio and uncle Silvio fascinated him at night. So, in 1980, he decided to follow the family tradition and today Lorenzo has taken over from his uncle in the ownership and management of Il Magnifico bakery, a laboratory and shop in the homonymous building located a stone’s throw from Piazza del Campo and the Duomo.«

Lorenzo, the third generation of a family of bakers, has been playing with flour since he was a child, within the ancient walls of the bakery, while carefully observing his father. Born on a small farm or San Marco outside Siena, he learned to love nature and its fruits and considers his father a teacher of life and work. He still remembers it when he would come home in the evening tired with bread for the family, wrapped in a white cloth. The emotion of this image is so strong that it induced him to follow in his footsteps. At first he learned the secrets of leavening, inheriting the precious mother yeast, the rest came by itself. Here the bread has always been smoothed by hand and placed un the oven with a “wooden stick” for eight 1 kg loaves.

The recipes for bread, panone and loaf are always the same. Of course the Tuscan bread is the master, however you also meet the charming Scottish bread (shaped in small squares, like a kilt. Homemade bread has a narrower slice and a six-hour levitation; the log is very light and crumbly with the soft dough of the ciabatta. The sense of humour is unleashed with the ciaccini and their thousand versions: made with extra virgin olive oil from Monte San Savino; 100 g; with sesame; tall; short; fat and so on.

What’s more: his typical Sienese biscuits and pastries are also famous outside the region and he bakes them all year round. Pan co’ Santi follows the classic recipe, with 24 hours of leavening, and it is worked in the old mixer. He engraves it with a wooden scraper (a wedge that the carpenter Alvaro gave him as a child) for a warmer cut. The brioche bread is a braid with chopped almonds, a little butter, a little brown sugar and Monsindoli acacia honey. The Panettone has a spectacular glaze, as well as being beautiful to look at. Cantuccini come in two versions and accompany Cantuccioni , extravagant biscuits with orange and lemon juice and a drop of Vin Santo. Do not miss the hot fried ciambellini in carnival season.

In conclusion, at any time here you will find a craftsman in all senses of the word. As his father used to say: ”You have to convey what you are in what you do”… there is something to learn for everyone!

Lorenzo Rossi

Il Magnifico

HERE WE HAVE TWO ''MAGNIFICENT'' MEETINGS TO RECOUNT: ONE WITH LORENZO ROSSI AND THE OTHER WITH HIS BREAD.... EVEN IN REVERSE ORDER, THE RESULT DOES NOT CHANGE.

Why this choice when he was still a boy?

The bread. It’s the bread’s fault. It makes you understand the value of work. I wanted to know how this food is born, so important that everything else is called a side dish. It is prepared at night, while everyone is asleep and grows, grows during leavening, then ends up in the oven and makes itself felt before coming out. Those who pass by a bakery at dawn can recognise it from the smell that spreads through the streets. Here, that smell of fresh bread, just out of the oven, announces that the life of a new day is about to begin. When I saw my father and my uncle go to work when it was still dark all this fascinated me and I wanted to be part of that world. After thirty years, I would not change the choice of that time.

How do you become a baker?

You can take courses but the real school is that of the shop: work at night, physical effort, meticulous respect for recipes, times, the rules of the shop. Then there is the clientele: if they like bread, flatbreads, biscuits and pastries, you see it immediately. And that is a great satisfaction that pays off any effort. The best is when word of mouth, perhaps among people who do not live in Siena and who have evaluated you with their tastebuds, brings people to the shop.

From bread to biscuits to pastries. Those from Siena are always baked in the oven. Just look at what’s on the shelves. Why?

Because they are the result of popular tradition, rooted for centuries in the habits of the city that continues to celebrate by bringing panforte, ricciarelli, cavallucci and all the rest to the table as it happened a hundred years ago. In Italy there are hundreds of types of bread, each linked to the grains produced in the area or to seasonal periods. For Sienese biscuits and pastries it is the same: production and consumption are linked to Easter, Christmas, the time of All Saints. Then there is a confectionery baking tradition that originates from home production and that we wanted to keep at the bakery because we bakers don’t live on bread alone.

Let’s talk about it: the cantucci?

EErroneously considered unique to Prato, even if in those parts they are a tradition with documented historicity. Cantucci are produced all over Tuscany, even at home. Be careful not to confuse them with biscotti because they are cooked in a single batch, while bis-cotti are cooked twice, as the name suggests. The ingredients are flour, sugar, eggs, almonds, Vin Santo, grated and squeezed citrus fruits, without butter or oil. It takes 20 minutes of cooking in the oven at 180° and they are ready to be cut while still hot. Call them what you want, Prato biscotti or Cantucci , but always bring them to the table.

Ciambellone

he shape gives it its name (from cymbella or cymbal). Simplicity is what makes it the prince of baked desserts. It is really good eaten immediately with a cup of tea but also many days after its preparation, when it is sublime dipped in milk for breakfast. Thirty minutes in the oven at 180° after mixing flour, sugar, vanillin, a pinch of salt, eggs, butter, extra virgin olive oil, grated and squeezed citrus fruits, and milk. Be careful because it’s not as easy as it seems. Eggs, for example, can generate an unpleasant aftertaste. This should be corrected with very careful dosage. Even the flour, if used excessively in relation to the other ingredients, makes the ciambellone too dense and difficult to swallow. These are tricks that are learned with experience.

Pinolata

Shortcrust pastry and custard. The best are not found in the bakery in large quantities because they are prepared only to order due to the custard, which must be very fresh and made with eggs. Supermarket products are not comparable because freeze-dried custards are used: that’s another story altogether.

Crostata

Shortcrust pastry and jam, only the finest. Not too sweet otherwise it can be sickening.

But which are more difficult: leavened pastries or the others?

All of them involve difficulties determined by the combination of ingredients and preparation times. Care is needed and when preservatives are not used, the processing and wisdom of old recipes are of great help. Proportions and sizes are valid in both artisanal and industrial production. The difference lies in the quantity of product, in the finish and refinement of the raw materials as well as in the freshness of the result to be consumed in a short time. The ingredients contribute to the taste. They must be good, genuine, fresh. It seems obvious but it is not.

So what’s wrong?

We live in an age of long-life snacks. Natural aromas succumb to the captivating taste of chemical aromas studied on computers to standardise consumption. Globalisation also flattens taste: what comes out of a box is considered “not good” only because your palate no longer has the memory tools to distinguish and compare.

But can you ”win” against snacks?

It is a choice not only of wallet but of convenience, or of saving time. The snacks are unwrapped and eaten perhaps after having kept them for months in the pantry. The baker’s product is fresh and should be eaten fresh. Industry on the one hand and crafts on the other. They can and must coexist. As with industry, artisans also stamp their signature on their product. It is the identity of the man who weighs, measures, kneads and bakes every night. Time is an ingredient.

Let’s go back to pan co’ santi.

Unlike schiacciata (flatbread), it knows no crisis, on the contrary it is also appreciated by foreigners and is produced for a few more weeks than in the past, as long as you can find the right ingredients. It is rich, calorific as a November dessert must be, difficult due to the necessary balance that must bind the various ingredients. Raisins and nuts must be high quality and in large quantities, an important factor also for the symbolism linked to the seasonality of the cult of the dead and of the saints. Carefully leavened with refined mother yeasts. If done well, pan co’ santi can be kept for many days. Ideal if enjoyed with young wine in early November.

Ricciarello.

Difficult. Sublime if well done. My first time was a disaster and yet I thought otherwise. I sinned in conceit, instead humility must be one of the ingredients of the good craftsman. For good ricciarelli you need excellent almonds, careful processing and, very importantly, good manual skills. Artisan ricciarello is externally very cracked but inside the crust the dough is not white. which would indicate excess sugar. Uneven height and size because it is handmade.

Like bread. But why the continuity between bread and pastries that is found only in the bakery?

The artisan baker always uses the same ingredients plus one: the ability to combine them in different ways to obtain multiple results. The artisan flours are not pre-prepared and the mother yeasts are often homemade and sometimes handed down for generations. Good Tuscan bread needs few ingredients including yeast, flour, water, and a person who kneads everything with intelligent flair and puts it in the oven.